How do you know that you’re growing up with parents with mental health problems when them suffering from mental health problems is all you know?

The truth is you don’t. You think it’s just the way they are, the way everyone’s parents must be. Without even ever hearing the term ‘mental health’ , or understanding what it means, it somehow becomes your everyday reality, your normality.

M Y M U M , D E P R E S S I O N & A N X I E T Y

Unbeknown to me, my mum suffered from depression and post-natal depression after the birth of my brother who is two years younger than me. The way this looked to me as a child growing up… My mum crying every morning while attempting to make our breakfast, and randomly bursting into tears at any given time throughout the day for no apparent reason. Being stuck inside for days on end in the heat of the summer holidays, in the dark, with the curtains drawn, my mum sat motionless on the sofa for what seemed like hours, my brother and I playing around her. If my brother and I started to bicker and fight with each other, she’d put her head in her hands, sob, and cry, “I can’t cope”. Words I would hear again on countless occasions. I quickly learnt that I had to try my best to not put pressure on my mum in order to avoid these moments of sobbing and overwhelm. I couldn’t misbehave, ask her for anything, and looked after my brother so she didn’t have to.

It was a complete role reversal. It was us who would go running to her to give her cuddles when she cried, reassuring her that everything was going to be okay. I effectively became my mum’s little counsellor. I remember I’d find her lying on her bed in the middle of the day sharing her woes with me. I think she thought I was too young to understand or remember what she was saying, but I took it all in, confused, feeling like I was expected to make her feel better somehow, but not having a clue how to. The reality is that my mum didn’t have anyone else to talk to. She was incredibly isolated, and in a way, we all were. My mum didn’t have any friends, or any family nearby. My dad saw to that. My mum was the most present, consistent, primary caregiver in my life. On her better days, it was clear she had the most amazing imagination. She’d encourage my brother and I to write and draw, on the backs of letters, envelopes and cereal box card as my dad didn’t approve of it. We’d play make believe games with her. She could make a simple trip to the local park feel like a magical adventure. She was the one who would wake us up in the morning, make sure we were clean, washed and dressed as best she could, look after us when we were unwell, take us to and from school, tell us bedtime stories and kiss us goodnight.

My mum wasn’t a ‘bad mum’ by any stretch of the imagination. She was very unwell and inevitably that had an impact on her ability to look after her children at times. There was never really any indication to me at the time though that my mum was unwell. I remember she once found me in the kitchen looking at some pills (probably antidepressants) she had been given thinking they were sweets. My mum took them off me, explained that they were not sweets, they had her medicine in that was meant for adults and not children, it would make me very sick if I was to eat one and that I was to never touch them again. Of course, I never did, but then, she never left them on the side again, until one day a couple of years later… I found them on the kitchen side, but not just one box, quite a few of them, there was a letter next to them and her car keys. All that felt odd and ‘different’. Different didn’t feel good.

It seemed like a normal day at first. Another day spent in the dark, curtains closed, my mum sat motionless on the sofa staring at a wall, me and my brother playing at her feet. I tried to involve her in what we were doing, tried to make her laugh, but despite my best efforts, nothing could break her helpless stare. Engrossed in play with my brother, I didn’t notice my mum get up and leave the room. But, suddenly she appeared at the door holding her car keys. She said, “Mummy’s got to go out somewhere now, Daddy will be back soon, you’ll be alright playing won’t you?” Somehow, I just knew. At 6 years old I had no understanding of death, but I had a very strong sense that something wasn’t right, my mum was going to walk out that door, fade into darkness and my brother and I would never see her again. I ran over to her, threw myself down on the floor, clasped onto her feet, cried, begged and pleaded with her not to leave. I told her that she couldn’t leave us, I couldn’t look after my brother on my own, that I loved her, that I needed her. I remember the relief when my mum put the car keys back in their usual place by the front door, said she wasn’t going to leave us, and not to tell my dad about this. It was just one of many things I couldn’t tell my dad about, and I never did, because I had seen what would happen to her if I did. Only a couple of years later in another one of our ‘counselling sessions’ my mum confirmed to me that she had plans that day to end her life that day and it was me that stopped her. Even before that I was carrying that burden though. I was forever living in fear that one day she would leave and I wouldn’t be there to stop her.

And one day, she did leave again, not for the same reason, but it left me with the same feeling. She found the strength to end her relationship with my dad on Boxing Day when I was 8. I don’t remember the words she said, it all blurred into a haze of the continual shouting around me, but whatever she said, it cut the atmosphere in the room. It told me that something big had happened and everything was going to change. It already had because for the first time it was my dad who was crying, not her! Not long after, she said she was going out to park with my brother as he was desperate to go out on his new go-kart. I wanted to go with her, but she wouldn’t let me. She told me I needed to stay with my dad, to give him lots of cuddles and that it was my job to look after him now. As usual, these were words I took on board very literally. I truly believed that it was now my sole purpose in life to look after my dad, yet nothing I tried seemed to stop him crying. My mum may well have only been headed to the park for a couple of hours that day, but I honestly believed in that moment that she had walked out my life for good. All of this just further heightened my fear of abandonment.

However, it was after my parents’ separation that I was able to come to an understanding that my mum had been unwell in some way. Apart from my dad, it was as though she became a different person. The crying with the curtains drawn stopped. She had an opinion. She had a say over what we were doing. She never had that before. She still struggled at times, but this noticeable difference in her told me that how she was before wasn’t truly who she was. Nonetheless, despite my mum being the main most consistent figure in my life, I never felt like she was truly there, or could be relied upon to be there for me. She may have been there in body, but emotionally she was unavailable to me.

T H E I M P A C T

It may sound harsh but it was as though both my parents were so consumed with their own difficulties most of the time that they were completely oblivious to the fact that I was facing some serious problems of my own. It never even occurred to me that if I had a problem in my life or was upset in any way, I could turn to my parents. So much so that when I was repeatedly sexual abused as a child, it didn’t even cross my mind that this was something I should be telling them. I was too young to understand what had happened to me, I only knew how it made me feel. My mum couldn’t cope when I came running to her with a cut knee, and I had a sense that this was so much bigger than that. So I didn’t tell. Not ever.

M Y D A D , B I P O L A R & A L C O H O L I S M

My dad. You’ve probably already got a sense that he is a story in his own right! While my mum could almost be relied upon for being consistently depressed, with my dad, you never knew where you were with him… People who knew him well would describe him as either being really up or down, with nothing much in between. For weeks or months he would sink into a deep, dark depression, which was mainly characterised by extreme irritability. As a family we were always walking on egg shells around him. Something as minor as crinkling a crisp packet could be enough to send him into an almighty rage. He was pent up, aggressive, mainly emotionally abusive, but physical at times. The most frightening thing about living with my dad was that you constantly felt as though you were just about to get hit. He would come right up, scream in your face, grab you by the arm, push you into a corner, raise his fist, and you’d almost be willing him to hit you because that seemed preferable to the constant fear of feeling as though you were about to be hit. He was lost and unreachable during those periods. He would become paranoid, his thoughts usually going along the lines that everyone was out to ‘get him’, even believing that the entire family were in on a plot to kill him.

As quick as he sank, all of a sudden, sometimes almost overnight, he could be as high as a kite. He’d be up at the crack of dawn, blasting an air horn to wake everyone up, and we’d come down stairs to him dancing around to bollywood music! He’d sing loudly and continually no matter where he was. He’d go round believing he was a popstar, would tell everyone he was, and would expect special treatment and offers as a result! He’d leave himself answer machine messages just so he could laugh at them later. He’d drive round erratically, sounding his horn and would shout at people in the streets for no apparent reason. Then there was the excessive spending. For someone who was usually very tight and frugal with money, all of a sudden he’d be booking expensive holidays, buying expensive items for himself (never for anyone else!) with money he didn’t have, as well as bizarrely buying bulk loads of items that we didn’t need. I will never forget the day when he cleared the shelves of the local supermarket buying every ready meal curry they had just because they were on offer and he was adamant we needed all of them. We had enough curries to feed the whole village and absolutely no space for them. We took them back to the supermarket, the shop workers expressing concerns about the manic and impulsive manner in which he bought them. When we later told my dad about it, he’d deny the whole thing, or blame us for not stopping him. That happened a lot. On the whole, this manic, larger than life character was preferable to the alternative dark, depressed, irritable and aggressive dad, but it really was one extreme to the other and you couldn’t keep up with him. It could also be quite embarrassing. He turned up to pick me and brother up from school wearing a blue wig and a hawaiian shirt once! All our friends would tell us that we were so lucky to have such a fun and cool dad. They never saw the flip side though. No one did.

Then there was the hallucinations, but of course I didn’t know that’s what they were at the time. He’d tell us that he’d been having a conversation with God in the toilet. He claimed to have seen seven donkeys walking down our street in the middle of the night and saw it as a sign of the Second Coming. He told us stories of him having a coffee with God and Jesus in our living room, and of talking to some angels in the local pub, though it was clear they weren’t just stories to him. As a child, I loved hearing these stories, but had no understanding at all that they weren’t true. I’d proudly tell my friends that my dad had met God and Jesus, and of course be laughed at and ridiculed.

It’s probably clear to a lot of people reading this that my dad had bipolar type 1, but that only became clearer to me as I got older. I remember in my teenage years following a storyline on Grange Hill of Annie and Barry Wainwright and their dad who had bipolar. That was a turning point for me in terms of understanding that my dad’s behaviour was probably the result of a mental health problem as opposed to being simply the way he was. As other family members read up on bipolar, they all came to similar conclusions to me. Following a very traumatic incident at home involving my dad when I was 14, my stepmum took my dad to the doctors. She saw my dad’s vulnerable state at the time as an opportunity to express her concerns regarding my dad’s mental health, specifically that he didn’t ever seem to be consistently depressed, but rather went through periods of extreme highs and lows, and that she felt he was displaying many of the symptoms of bipolar disorder, giving examples. The doctor seemed to support her view, but said he would have to be referred to a psychiatrist for diagnosis. A referral was made to the CMHT, but weeks later when the letter arrived in the post inviting my dad to an assessment, it was met by pure outrage! My dad didn’t attend, claiming that there was nothing wrong with him, it was all part of the plot we were in on to convince him he was ‘mad’ and cause him to kill himself. According to him, we were the problem, not him.

Alongside all this was my dad’s alcoholism. My dad was an alcoholic my whole life. Some of my earliest memories were of him being sick and passed out on the floor. He drank when he was high. He drank when he was low. It was probably the only real constant in his life, and it was also all I ever knew. As with most of the other difficulties my dad faced in his life, he was in a state of almost continual denial, and everyone else was to blame besides him. I lost count of the amount of times I heard the spiel that he didn’t have a problem because he wasn’t as bad as so and so down the road, and the worst ever – that we were the reason he drank. There were what felt like breakthrough moments with him, in which he’d admit he had a problem and would seek help. We’d cross our fingers and pray that this was the end of our life of misery with him. However, it was always short-lived. He’d gather us all round in the morning to hear a speech about how he was never going to drink again, he’d go to an AA meeting, and yet we’d find him in the pub by lunchtime. Mental health difficulties and addiction often intertwine, and I always saw that as being very much the case for my dad, even if he didn’t!

M E N T A L H E A L T H D I F F I C U L T I E S D O N O T E X C U S E A B U S E

It’s hard though, as I said at the beginning, to distinguish what was the result of alcoholism, the result of mental health problems and what was my dad, when all I ever knew was the three merged together. Taking into account that my dad’s mental health problems and struggles with addiction did impact his behaviour significantly helps me to understand it and make sense of some of the traumatic things that happened during my childhood, but it’s important to know that it doesn’t excuse it. I’ve since come across many others with mental health problems of a similar nature to my dad’s and they have never and would never behave in the abusive way he did towards others, particularly those closest to him. Also, I honestly believe that most kind-hearted people, even if they didn’t fully believe at that point that they were suffering from mental health problems, would still seek support at the request of their friends and family, especially if they were told that the difficulties they were experiencing were negatively impacting on their relationships with those closest to them. The way I look back on it now is that my dad was not to blame for the fact that he was suffering from significant mental health problems which inevitably had an impact on my childhood, but he was to blame for not seeking or accepting help.

H O W M Y P A R E N T S R E A C T E D T O M Y O W N S T R U G G L E S W I T H

M E N T A L H E A L T H

I would like be able to say that my parents’ experiences of mental health difficulties made them more aware and sensitive to the potential signs of poor mental health in their children. However, it seemed to have the complete opposite effect! They almost became blind to potential signs that me and my brother were struggling. There was a sense that they needed to keep telling themselves that we were fine, that their own difficulties had not affected us in any way. There was also a sense that we had to give them the impression that we were absolutely fine because they clearly had so many difficulties themselves that they were struggling to cope with, we couldn’t add to them, so just had to be ‘okay’.

Both my parents never noticed that I had developed an eating disorder from the age of 7 and became severely underweight until it was pointed out to them by someone outside the family when I was a teenager. And despite me being diagnosed with anorexia under CAMHS and following a treatment plan for it, my mum has never accepted that I’ve ever had an eating disorder. There was also no sense of them having to pull together and be strong for me when it became clear that I was suffering from mental health difficulties as a teenager. I remember the day my dad came to my CAMHS appointment for the first (and only) time, he went straight home and drank himself into oblivion. From that point on when anyone picked him up on his drinking, he would try to justify it by openly blaming me, asking what people expected when his daughter was ‘killing herself’ and ‘bringing shame upon the family’. My mum would never blame me for the mental health difficulties I’ve experienced in my own life, but has always had a tendency to want to brush things under the carpet. In recent years, it has come as a complete shock to her when I’ve had to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, despite the fact that there were very clear signs that this was on the horizon.

I grew up with the impression from my parents that it wasn’t okay for me not to be okay. Now I see that this was more a case of my parents trying to escape from the guilt and responsibility they felt for the difficulties I’ve faced in my own life. As far as I’m concerned, that guilt is completely misplaced. Despite everything, I have never blamed my parents for my own mental health difficulties.

T H E I M P A C T : O V E R R E S P O N S I B I L I T Y

One of the main things that rubbed off on me as a result of growing up with parents with mental health difficulties was a sense of over-responsibility. I was effectively a parentified child. For most of my life, I felt more like a mother to my brother than a sister. That sense of over responsibility extended outside the family. Putting others first wasn’t a conscious effort for me, it was all I knew. It has been something I’ve had to work on a lot since. As children often do, I would always blame myself for any issues experienced by family members, because blaming myself gave me an illusion of power and control over the situation. If I blamed myself, it made me feel as though I could do something about it. Particularly in relation to my dad, I grew up thinking that if I could be the ‘perfect’ daughter, then all his problems would miraculously disappear. This belief provided never ending fuel to my already obsessive perfectionistic nature, because all the while my dad’s issues persisted, it told me that I must try harder!

T H E I M P A C T : S E L F – N E G L E C T & A H A R D D E C I S I O N

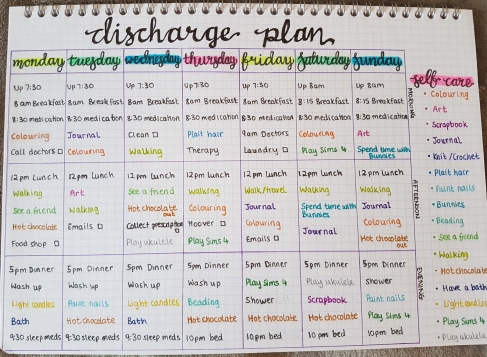

As I hit adulthood, it soon dawned on me that I had spent so much of my life absorbed in trying to help others that I had completely neglected myself and my own mental health. I had been running away and hiding from some traumatic events I had experienced throughout my childhood and the unresolved issues these experiences had left me with. I couldn’t run anymore. At the cusp of adulthood everything I had suppressed flooded out and hit me in the face. I had no choice but to face it, and I knew that in order to do that I needed to re-address the balance in my life.

I made the difficult decision to cut my dad out my life in order to focus on myself. It was a decision that felt laden with risk, because every time I attempted to distance myself from my dad, he threatened to end his life, and had taken an overdose on occasion. I had to get myself to a place where if that was to be the consequence of my decision, I would have to find a way to live with it. Needless to say, that didn’t happen. Cutting contact with my dad was one of the most difficult decisions I’ve ever made in my life, but eventually it came to be a turning point for me. I came to the conclusion that I had spent so much of my life living to save my dad that I had completely lost myself in the process, and you can’t help someone who does not want to be helped, and won’t help themselves. Interestingly, it was only when living abroad, separated and cut off from all former friends and family that my dad made some positive strides forwards in his own life, with his drinking at least!

T H E I M P A C T : A S E N S E O F F A I L U R E F O L L O W E D B Y

A R E N E W E D S E N S E O F P U R P O S E & M E A N I N G

At first, when it became apparent during adulthood that I too was suffering from a multitude of mental health problems – now diagnosed with Dissociative Identity Disorder, Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Severe Depressive Episodes and a history of Anorexia Nervosa, I was filled with a sense of failure. If there was one promise I made to myself growing up, it was that I was not to become a product of my situation. I was not going to turn out like my dad and make the same mistakes that both of my parents made. I was determined not to allow my family circumstances to dictate my life’s chances. Overwhelmed and consumed by the severity of mental illness, I believed that promise to myself to be broken, shattered alongside the series of traumatic events that had marred my entire existence. With time I’ve come to see though that it’s not life’s difficulties that define you as a person, it’s how you choose to face them and seek to overcome them. Unlike my parents, facing up to my mental health difficulties, seeking support and working through the traumatic experiences that have shaped my life has made me acutely aware of the mental health problems that people face. With that awareness comes empowerment. My own journey has led me to embark on a new peer support career path in which I endeavour to use my lived experience of mental health to help others.

M E S S A G E T O O T H E R S G R O W I N G U P W I T H A P A R E N T O R

P A R E N T S W I T H M E N T A L H E A L T H P R O B L E M S

My advice to anyone out there who is growing up with a parent who is experiencing mental health difficulties… Please know that it is not your fault. Be there for them. Listen and be understanding, but know that it is not your responsibility to look after them. Know that you matter, first and foremost. Know that anything in your life that feels like an issue to you is significant.

And know above all else that it’s okay not to be okay.

Lorna ♡

PS: Remember…